Turns out, long-forgotten cans of salmon have ended up giving us a backstage pass into Alaska’s marine past. These overlooked tins have now become a goldmine for scientists, helping them track how Alaska’s ocean life has changed over the last 42 years. And as a bonus, they’ve shown just how important (yep, really important) those tiny marine parasites can be in keeping nature on track.

The unexpected value of old salmon cans

A study published in April 2024 in the journal Ecology and Evolution tells the story. Originally, these cans were just set aside for quality checks, but researchers from the University of Washington—headed by Natalie Mastick and Chelsea Wood—turned them into a treasure trove of ecological info. By digging into these preserved fish, they managed to piece together data on Alaska’s marine scene spanning 42 years.

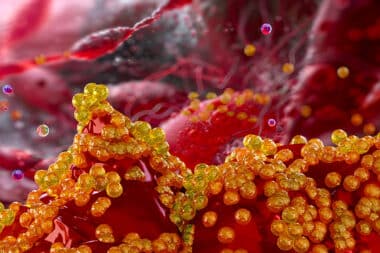

One particularly surprising twist was finding anisakids, a type of small marine parasitic worm, inside the salmon. These little guys aren’t out to cause harm; instead, they act like a natural “check engine” light (showing us that the ecosystem is running smoothly). As Chelsea Wood put it, “The presence of anisakids is a signal that the fish on your plate comes from a healthy ecosystem.”

After 4 Years of Remote Work, Their Verdict Is Final — and It’s Making Waves

Getting to know parasites in the wild

Anisakids have quite the busy life: they start off in tiny krill, move up to bigger fish like salmon, and eventually wrap things up in the guts of marine mammals. This winding lifecycle makes them great little indicators (or bio-indicators, as scientists say) of how stable the marine world is.

The team looked closely at 178 cans featuring four species of salmon. They broke it down like this:

- 42 cans of Chum (Oncorhynchus keta)

- 22 cans of Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

- 62 cans of Pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha)

- 52 cans of Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka)

All these fish came from spots like the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay, snagged between 1979 and 2021.

What the researchers did and found

Even though the canning process had taken its toll on the fish, the scientists were still able to work out the number of worms per gram of salmon. This clever approach let them track changes in parasite numbers over time. They found that chum and pink salmon had seen a rise in these worm counts, while coho and sockeye numbers stayed pretty steady. These differences hint at varying relationships between the parasites and their fish hosts.

Natalie Mastick commented, “This increase could indicate a stable or recovering ecosystem, with enough suitable hosts for anisakids.” (Basically, it tells us the environment is holding its own, giving the parasites plenty of places to call home.) These findings help us see more clearly how parasites team up with their hosts and shape broader natural patterns.

What this means for future studies

This study isn’t just a one-off neat trick—it opens up new ways to look at long-term changes in the oceans. By treating old, expired canned goods like ecological time capsules, researchers can now track shifts in marine populations over decades. This method also gives us a fresh angle on how climate change might be nudging marine life and sheds light on the tangled relationships between parasites, fish, and marine mammals.

In the end, this discovery shows that sometimes, science finds its biggest clues in the most unexpected places. Those forgotten cans have given us a rare peek into Alaska’s natural story, proving that every little piece of the puzzle matters when it comes to understanding our environment.