Deep down in the Atlantic, there’s a hidden danger that’s been lurking out of sight for decades—over 200,000 barrels stuffed with radioactive waste. This heavy reminder of past practices now has people worried about marine life (and even our own health). Even though dumping radioactive waste into the ocean is banned today, remnants from back in the day still sit undisturbed on the seabed, leaving many to wonder what might happen over the long haul.

Looking back on old methods

Since the late 1940s, dealing with radioactive waste wasn’t an easy job. Back then, scientists and policymakers thought the vast ocean was the perfect spot for dumping waste because it was huge and seemed empty. The abyssal plains, resting at an eye-popping depth of 13,123 feet and hundreds of miles offshore, were once believed to be barren (in reality, they’re teeming with life). This mistaken belief paved the way for decades of ocean dumping.

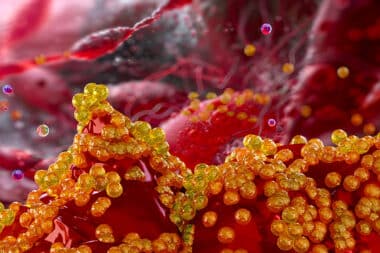

Between 1946 and 1990, more than 200,000 barrels of radioactive waste were dumped into the Atlantic. They were sealed in materials like bitumen and cement (designed to keep leaks at bay). But as we got to know our oceans a little better, doubts began to rise over whether these seals would hold up over time and what might occur if radioactive material started seeping out into a surprisingly lively ecosystem.

Growing anxieties and new rules

Once scientists discovered that the ocean was far more vibrant than everyone imagined, worries about the buried barrels started to mount. The thought that they might eventually leak radioactive material into nearby waters set off alarm bells among environmentalists.

In 1990, regulators stepped in under the London Convention, officially putting an end to the dumping of radioactive waste into the ocean. Still, those barrels remain on the seabed, with their current state unknown after so many years underwater.

Where things stand and what science is doing

It’s been 35 years since the last barrel was dumped in the Atlantic, and we still aren’t sure what condition they’re in. No one has yet attempted to pull them up or thoroughly assess their state. This lingering uncertainty has now spurred scientists to take a closer look.

This summer, an interdisciplinary mission is gearing up to collect samples of sediment, water, and local sea life in the dumping zone (to check for any radiological risks). But before the sample gathering can get rolling, researchers need to map out exactly where these barrels are hidden.

Charting the unknown with technology

A new project called Nodssum is about to kick off, bringing together teams from CNRS, Ifremer, and the French oceanographic fleet. Their mission? To survey roughly 2,317 square miles of abyssal plain using high-resolution sonar and an autonomous submarine named UlyX—one of the few subs capable of handling such extreme depths (pretty impressive, right?).

This first phase will pave the way for a follow-up oceanographic campaign that will closely examine the area right around the barrels—a key step in understanding just how much of a bother these old waste containers might cause.

Understanding how humanity’s historical choices continue affecting our world today serves as both a cautionary tale about repeating similar mistakes moving forward while also pointing out opportunities for science to help lessen unintended side effects from those decisions made long ago at sea’s edge without full knowledge or foresight into future implications they might bring forth over time if left unchecked indefinitely beneath surface currents swirling silently above them still yet unseen until now once again being brought back into light through modern exploration efforts underway soon ahead anew once more again soon thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereafter shortly thereafter thereby bringing forth new insights gained anew once again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once more again soon ahead anew once more again!